Jamie Hawkins, only child of an old mother, had a hump on his back and one leg three inches shorter than the other, so that he walked like a crab. His heart, his mother said, was so big it nearly cracked his ribs. It was full with wanting to love so much that his chest ached with the trying. But Jamie, with his crabwise way and his turn-aside head, his quizzical look...he opened himself to a world that span on by without a backward glance.

The spirit is not a vacuum, and where people would not speak to him, the essences of things did. Jamie grew up limping round his own island, analyser of little things, observer of single blades of grass for their shape, their greenness, their smell when crushed. In this way, he collected images, sounds, words, seeing a closeness between people that he felt but did not know.

He would sit at the window, the chair turned from the desk so that his body faced it straight. He wrote left-handed, the wrist curled round, fingers forcing sinister loops that meant little. He was not happy; neither was he sad. He existed in a state of sleepy limbo, where his food arrived on a tray brought by his mother, and his contact with the outside world was through glass, misted.

Why is it that lack of fortune attracts, like north and south, more misfortune? Why is there no balance in things? Maybe, had he been straight, with both legs the same length, his mother would have stayed with him longer. As it was, when his food did not arrive at suppertime one bright summer evening, Jamie went to find her, and discovered she had died. Quietly. No fuss. Given out.

There was something in her calmness, in the stillness of a hand on the floor, that moved Jamie beyond loss. This was where poetry was. At the end of things, where they were full to bursting with life, and life had given out, simply because it could not be held in any longer.

...

At first sight, on his first morning, the mortuary didn't seem the best place to find real poetry, which was the only kind Jamie was after. There was not much depth to the bleached metal surfaces, the gaping gutters, and the coils of pale tubing. But he had time stretching like an empty desert before him; the trick was going to be finding the hidden rivers.

...

She looked asleep. Strands of her hair, a damp greenish-blond, hung together in lank curls as though wet, one flattened across her forehead. Her eyes were not quite closed, as though she was still watching between her lashes...but the glint was gone, flattened, old glass. The dark lashes cast shadows down her cheeks. Her mouth was half-open, petulant, protesting.

...

Purchase the issue to read more of this piece and others

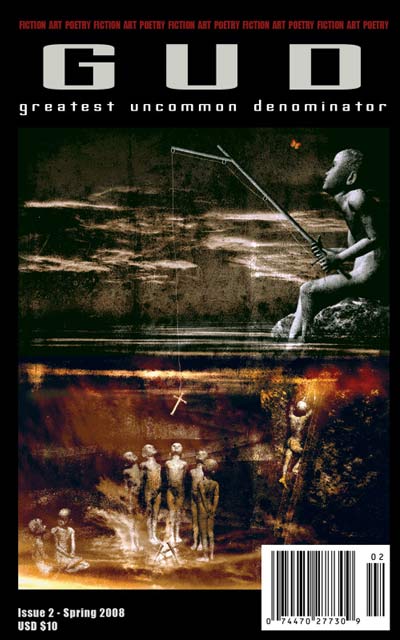

While I found the cover off-putting for a handful of reasons, once inside I was caught in the flow of the narrative. Roberts realizes her players well, showing multiple sides to mythic characters, and the details she puts into this historical re-imagining of "The Epic of Gilgamesh" really bring the story to life.

While I found the cover off-putting for a handful of reasons, once inside I was caught in the flow of the narrative. Roberts realizes her players well, showing multiple sides to mythic characters, and the details she puts into this historical re-imagining of "The Epic of Gilgamesh" really bring the story to life.